An herb garden is its own theme, but you can specialize by choosing only herbs from the Bible, herbs for teas, or herbs for dyes. Or you can tuck herbs into other specialized gardens. Use the designs presented here as inspiration for your own garden, and feel free to mix and match, enlarge or shrink, or change the shape of the beds:

- A beginner's garden: Start your garden with a raised bed of basil, campanula, catmint, chives, cilantro, dianthus, dill, lavender, parsley, rosemary, sage, tarragon, and thyme. The sage will eventually get too big; transplant it and use the space for more parsley. If the dianthus rebels against your hot summers, experiment with licorice plant. Build this garden at least knee-high with landscape timbers. If you place a board atop one edge, you can sit and admire your lavender. Located just outside the kitchen door, this garden gives you quick access when tarragon chicken is on the menu.

- A garden for bees and butterflies: If you enjoy watching butterflies float and bees industriously wallow in pollen, consider planting a garden of their favorite herbs: boneset, borage, buddleia, catnip, chamomile, coneflower, dill, hyssop, lavender, monarda, oregano, and parsley. The flowers of nearly every herb attract bees, so ruthlessly lop off flower buds before they open if you react severely to stings. If you collect herbs on an overcast day, the bees will be more laid back. Many of the plants that attract butterflies also supply food for their larvae. (As with second marriages, attracting butterflies is a case of "love me, love my children.")

- Some male butterflies congregate in mud puddles because, during mating season, they need the sodium and other minerals that leach from the soil. Here, poorly draining soil, otherwise cursed by gardeners, is ideal. (You'll need to make mud with the garden hose on days that it doesn't rain.) Set out a shallow dish of water for butterflies that don't patronize mud baths.

- A Shakespearean conceit: Conceit can mean an elaborate metaphor, or a fanciful idea, the likes of which herb gardeners are quite fond. To create a relaxing place for reading or meditation, choose plants that flower in restful shades of blue and pink, such as bay, chamomile, dianthus, honeysuckle, hyssop, lavender, myrtle, orris, rose, and rosemary. (Bay and rosemary aren't cold hardy in most of the country, so grow them in containers and bring them inside during the winter.) Shakespeare's plays and poems are full of more plants than anyone could cram into a single garden, so the list of substitutions is limited only to the time you have to spend perusing the "The Greatest Works Of." A formal design is less distracting than an informal garden's random patterns.

- A culinary garden: If you love to cook, grow your herbs where you can snatch a handful easily in all kinds of weather. Consider including basil, caraway, chervil, chives, cilantro, dill, garlic, mint, nasturtiums, onions, parsley, rosemary, sage, thyme, and winter savory.

- A patio garden: Herbs are heavily scented, but most of them don't release their delectable You can mow some newer, dwarf varieties lower fragrances into the air by themselves. They must be crushed or at least brushed against, so plant them where you can finger them or even dance on them. Consider including dame's rocket, fennel, honeysuckle, jasmine, juniper, lamb's ear, lavender, rosemary, soapwort, sweet Cicely, sweet woodruff, thyme, and valerian. Plant fennel and soapwort in containers because both species are invasive in a friendly climate.

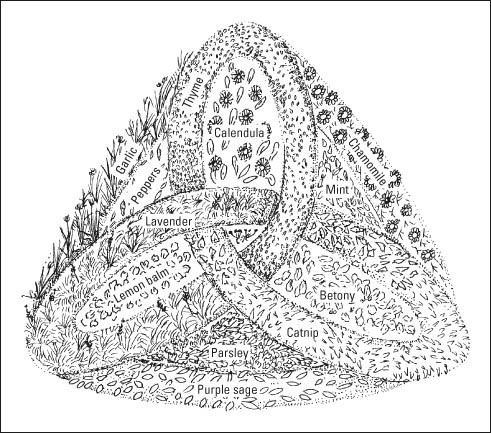

- A knot garden: Knot gardens were basically intended to show off the wealth (or leisure time) of their owners. Even if you have space and time to spare, you may want to put your garden to a more productive purpose. These gardens are lovely to look at, however, and a relatively simple knot design (as shown in Figure 1) allows you an ample variety of herbs useful for medicine and tea. The traditional knot in the center, based on an equilateral triangle, is a triquetra (also known as a shamrock design).

>

Figure 1: Achieving this knot design is easier than it looks.

- Consider how much you plan to harvest any of these herbs before you plant, since some sections are bigger than others. (If you harvest too much of a knot, you'll "untie" it!) You want the herbs to knit together quickly, so plant them — annuals in particular — close together. You can make your plants appear to grow under and over each other by pruning one plant on the underside of its growth and pulling the long top growth over the adjacent plant. Keep the whole design to 5 feet across or less if you want to have any hope of reaching plants near the center without treading on the bed.

- A mixed garden: Mixing herbs with vegetables or flowers isn't a radical technique. English cottage gardeners were doing it centuries ago. Consider mixing lovage, borage, and savories with bush beans and onions; southernwood, mint, and chives with eggplant, cabbage, carrots, and radishes; monarda with tomatoes and potatoes; and, basil, tansy, tarragon, and calendula with tomatoes squash, peppers, and asparagus.

>

dummies

Source:http://www.dummies.com/how-to/content/designing-an-herb-garden.html

No comments:

Post a Comment